Medieval World: Culture & Conflict picks up where its sister magazines – Ancient Warfare and Ancient History – leave off. The publication features the rich history and material culture of the Middle Ages – broadly conceived geographically and temporally – expanding on the contents of the popular Medieval Warfare magazine. Through well-researched and lavishly illustrated articles, this accessible publication brings to light cultural activities in local and global contexts, historical figures and events, as well as political, religious, economic, and artistic facets of the Middle Ages..

Medieval World Culture & Conflict Magazine

Editorial

MARGINALIA

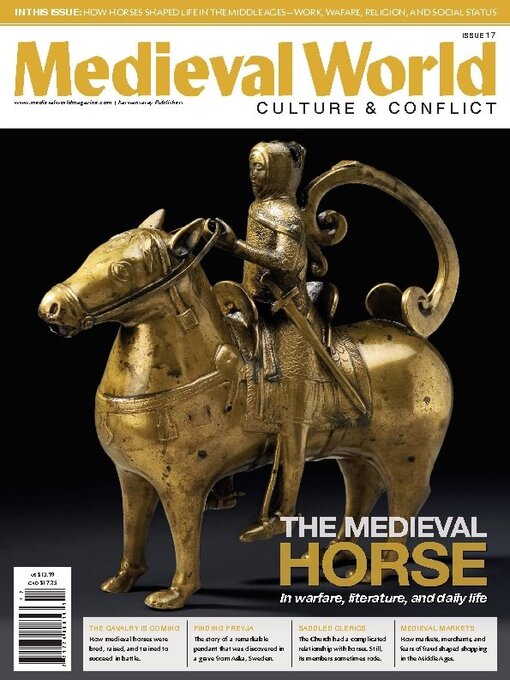

FREYJA'S FINAL RESTING PLACE • In the 1920s, an unassuming location in the heart of Swedish farm country suddenly began to reveal many surprising secrets beneath its soil. Among these finds was a now world-famous relic thought to represent the Norse goddess, Freyja.

FREYA'S SERVANT • The Völva's grave at Aska

Gamla Uppsala

Modern adaptations

CHIVALRY AND VIOLENCE • Chivalry is most often seen as medieval society's means of controlling knightly violence. By encouraging capture and ransom over killing, a sense of fair play and a distaste for trickery and cheating, and by emphasizing the Christian duty of the knight to protect the weak and helpless, this view of chivalry makes the knight a less violent and bloody-handed figure than, say, the Viking. But was this really the case?

FROM COURSERS TO HACKNEYS • In the Middle Ages, riding was a social activity. Generally speaking, noble men and women rode horses, as did those who had enough money to buy one and needed it. Those whose status or occupation did not require horse-riding either walked or stayed at home. It was also possible for those with status and money to travel in a litter, usually placed on the back of horses or mules. The poor could travel in a cart, too, but the noble would not travel this way lest it would compromise their status.

Death by horse

Horses in medieval China

THE MIRROR OF MAN • The horse is one animal most intimately associated with the Middle Ages through the image of the mounted knight. Medieval chivalric culture relied on horsepower to such an extent that, in many European languages other than English, the word for “knight” was either derived from the word for the horse (caballarius, chevalier, caballero, etc.), or the rider (ritter in German). But the warhorse was not the only type of horse that medieval people encountered – broodmares and working horses belonged to an entirely different order of animals. Still, knowledge about the horse's behaviour and psychology underlies many medieval beliefs and narratives that may appear unlikely and even bizarre to a modern reader.

FIGHTING ON HORSEBACK

The mounted man's horse

THE HORSE IN BYZANTIUM • In AD 330, the capital of the Roman Empire moved from Rome to the lavishly renovated city of Byzantion. The city was renamed Constantinople, after the reigning emperor. This is sometimes seen as the creation of a new entity, the Byzantine Empire, but the people of that land never recognized the term. Momentous as it seems to us, to them it was just the continuation of a state that had celebrated its first millennium less than a century earlier. Over the next millennium, many things changed for the people of this empire and for their horses, but not very quickly.

THE RIGHT WAY TO RIDE • Mastering the art of horse riding and wielding weapons while on horseback has been difficult throughout the ages. It is, therefore, not surprising that handbooks on military equitation in ancient, medieval, and renaissance history spend many paragraphs on this subject. Drawing on ancient and medieval sources, this article discusses several important developments in equitation that...

Issue 17 - 2025

Issue 17 - 2025

Issue 16 - 2025

Issue 16 - 2025

Issue 15 - 2024

Issue 15 - 2024

Issue 14 - 2024

Issue 14 - 2024

Issue 13 - 2024

Issue 13 - 2024

Issue 12 - 2024

Issue 12 - 2024

Issue 11 - 2024

Issue 11 - 2024

Issue 10 - 2024

Issue 10 - 2024

Issue 9 - 2023

Issue 9 - 2023

Issue 8 - 2023

Issue 8 - 2023

Issue 7 - 2023

Issue 7 - 2023

Issue 6 - 2023

Issue 6 - 2023

Issue 5 - 2023

Issue 5 - 2023

Issue 4 - 2022

Issue 4 - 2022

Issue 3 - 2022

Issue 3 - 2022

Issue 2 - 2022

Issue 2 - 2022

Issue 1 - 2022

Issue 1 - 2022